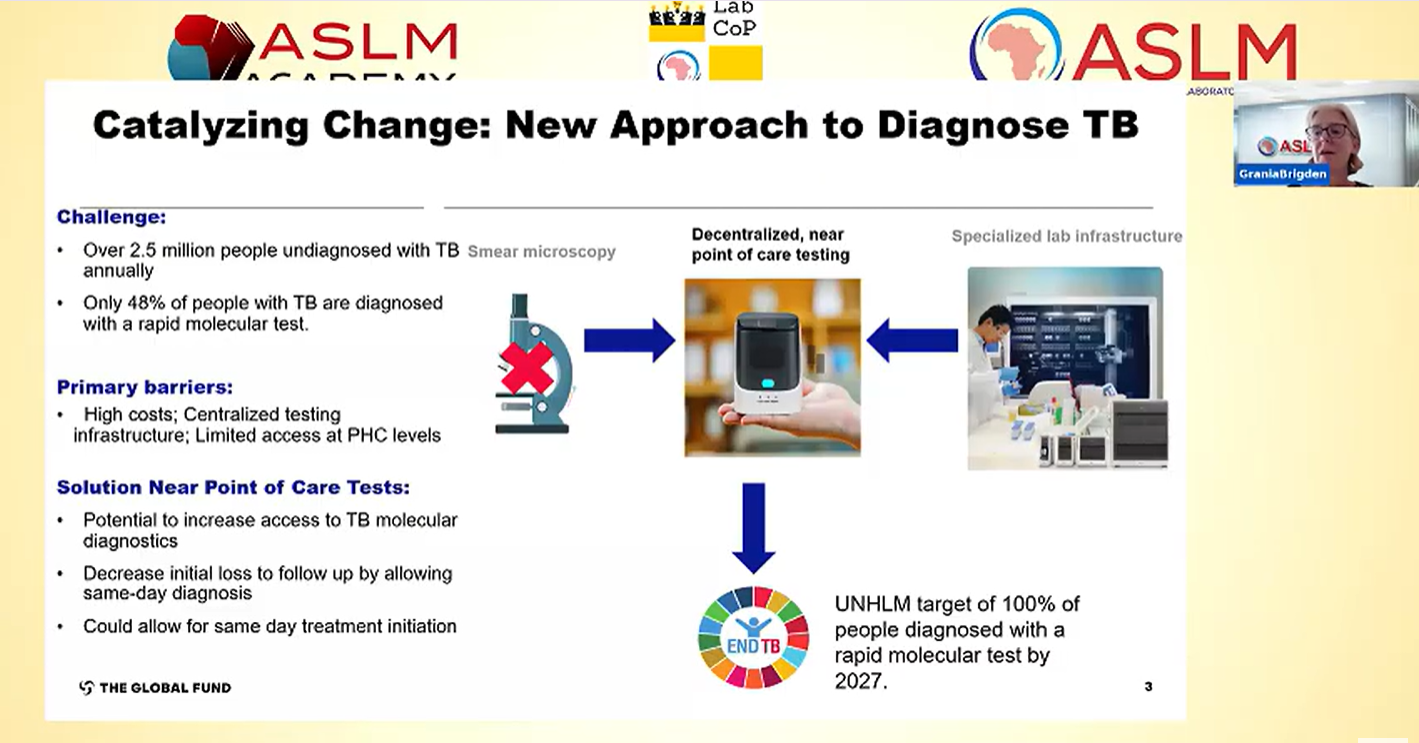

Access to rapid TB diagnosis remains a challenge. Globally, just over a third of TB testing sites have access to a WHO-recommended rapid diagnostic (WRD) test. Where testing is available, it is often in urban, centralised locations, away from the primary healthcare facility where people with TB first seek care. Moreover, the reliance on sputum samples for bacteriological confirmation of pulmonary TB limits access to WRDs for people who cannot produce sputum, such as children, the elderly, and those living with HIV. However, there is hope on the horizon as a new generation of molecular swab-based technologies, suitable for deployment at primary health facilities is anticipated to reach the market in 2026.

The devices require minimal infrastructure, are battery-powered, have simplified procedures, and are projected to be more cost-effective than current tools. Their potential to expand access to testing in remote, and hard-to-reach areas has generated considerable excitement. As these new tools are introduced, coordinated and comprehensive planning, informed by lessons learned from roll-out of similar tools in the past, is essential. Our analysis of progress made by LabCoP countries in implementing current TB diagnostic tools showed that funding, staffing, supply chain and sample transport networks pose significant barriers to implementation. Therefore, key enabling factors to translate policy into implementation include:

Advocacy: Early and coordinated advocacy is essential to advocate for lower prices, and ensuring adequate funding and equitable access to these tools. Engagement of national civil society organisations in implementation discussions is key to keep governments accountable to providing access to rapid testing for all people with TB. Sustained advocacy ensures that actionable implementation plans are developed. Additionally, coordination among global and regional partners is important to facilitate efficient and cost-effective uptake of new tools guided by the local context.

Funding:TB programs are currently operating in a challenging environment due to limited international/donor funding available for program activities. These funding cuts have negatively impacted TB diagnostic services, particularly active case finding, staffing and sample referral across most African countries. As diagnostics are central to the End TB Strategy, it is essential that they remain a priority. Programs need to advocate for inclusion of these costs in national budgets to ensure continuous access to needed TB testing services for all people with TB. Civil society organisations play a valuable role in supporting TB programs in their efforts to secure increased domestic funding for TB control.

Diagnostic network optimisation: These new tools build on a diversified landscape of TB diagnostics, allowing programs to select the most appropriate solutions tailored to the needs of their network. However, the challenges and requirements of the diagnostic network vary significantly between countries, and even within regions or districts of the same country. Therefore, it is crucial for programs to know their network, know what the gaps and challenges are and strategically allocate resources towards interventions that yield the highest impact. Optimising diagnostic networks will be critical for determining necessary adjustments in capacity, test centre locations, or sample transport systems to support informed decision-making.

Comprehensive workplans: Programs must carefully consider the potential impact of changes to the diagnostic algorithm particularly on workflows and reporting processes. Proactive planning and early engagement of stakeholders including the community, private sector and other health programs is essential to address each aspect of the TB care cascade from patient identification to linkage to care. Importantly, due to the different sample type used for these new tools, careful attention should be paid to the clinic and laboratory workflows, and consider factors such as staffing, logistics, supply chain, sample transportation, data management, and quality. Accordingly, it is important to develop a comprehensive transition plan that incorporates clear communication, training and monitoring and evaluation to ensure smooth implementation.

Data management: Effective linkage to care and data management are critical considerations. As these new tools will be placed at lower tiers of the health system, it will be essential to strengthen both data recording practices and sample referral processes for reflex rifampicin testing. It will be important to connect these tools to laboratory and patient management information systems for timely patient management and enable monitoring of quality indicators such as turnaround time, error rate, and positivity rates.

Health systems integration: To achieve sustainable adoption and successful scale-up, it is essential to integrate these tools into existing health system strategies and operational workflows. Careful consideration must be given to how such tools are incorporated at the primary health facility level. For instance, their alignment with point-of-care HIV, malaria, or syphilis testing workflows, or more broadly, policies related to HIV, syphilis, hepatitis, or diabetes, to facilitate the integration of patient pathways, algorithms, staffing, sample referral, quality assurance, and supply chains.

To support countries to bridge the gap between policy adoption and implementation, ASLM has partnered with the Global Fund, Gates Foundation, Clinton Health Access Initiative, the Foundation for New and Innovative Diagnostics and the Diagnostics Equity Consortium to assess market conditions and diagnostic network readiness, enhance CSO networks, and develop implementation roadmaps. In quarter three of 2025, ASLM organised two webinars on near point-of-care technologies to inform stakeholders and reinforce the message to “know your network” to select the most suitable tools for addressing country-specific gaps. Additionally, in collaboration with the Global Fund, ASLM will host a meeting for 13 countries identified as early adopters of these new tools to support development of implementation plans and co-creation of roadmaps for reaching universal access to WHO-recommended rapid diagnostics.

Additional reading:

https://theunion.org/news/us-funding-cuts-negatively-impact-tb-care-and-prevention-across-africa

nPOC publication: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.07.03.25330836v1

nPOC webinars: https://aslm.org/resources/p-labcop/to-tuberculosis/?srch=August%202025